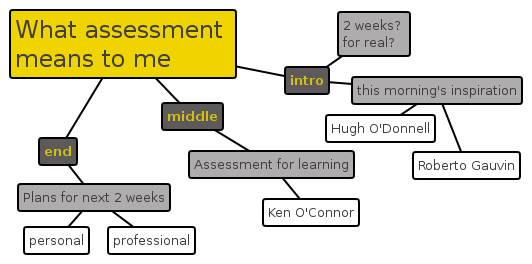

Listen to these ideas. (Go here to see a mindmap of this podcast and links to resources I refer to in it or just keep reading normally. Whatever turns your crank.)

[haiku url=”http://www.tracyrosen.com/leadingfromtheheart.org/wp-content/uploads/podcasts/assessmentAug9.mp3″ title=”Why I don’t do zeros”]

Image: from Not So Good by zephyrbunny, found on flickr and made available through a creative commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike license

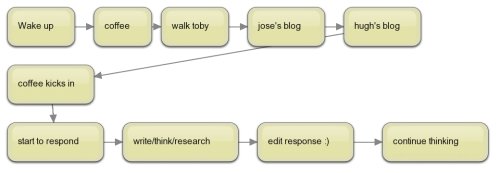

It’s Saturday morning, a little over 2 weeks until the school year starts again for teachers at the New Frontiers School Board, where I work. My mind lately, as it usually does around this time of the summer, has been shifting from summer to practice, and this morning it opened up to assessment. Here’s the flow chart of how it hit this groove:

Mind Map made with Bubbl.us

Mind Map made with Bubbl.us

And here is that comment I made over on Hugh O’Donnell’s post (which you better go over and read if you want any context):

That’s right, not radical at all. We do NOT need to give zeros and, I’m sorry, but the excuse that we’ve got so many initiatives thrown at us warrants the practice? (the practice = completely demoralizing children and doing nothing to help improve their learning) Come on. A zero as feedback gives me no hope.

I really began to learn the art of assessment about 5 years ago, when I met Ken O’Connor at a conference in Ottawa. And then I started to read everything I could about it, which I’m still in the middle of doing

So I guess I’m one of those teachers who read. And you know what I do when I am reading? I do it publicly – I carry the book around with me, I talk to others about what I am reading and about how, if at all, it is helping to change my practice.

So it DOESN’T need to be top down. If we sit around waiting for someone else to do something, well…wouldn’t it be lovely for there to be the perfect piece of grading policy to fall from above that all teachers would embrace and follow. (where’s the smiley guy for sarcasm?) Un-unh. I’m not waiting for policy to inform my practice. I prefer to focus on my practice and allow it to inform policy.

I googled Ken O’Connor and found this. An administrator’s notes from one of his sessions from last year. I particularly like the list at the end – repair kit for grading.

http://carnets.opossum.ca/roberto/2007/10/ken_oconnor_excellentevidemmen.htmlhe he – first comment of the weekend. Guess the coffee is kicking in

(and that’s the edited version…)

Assessment informs learning. I assess before, during, and after units of study so that my students and I know where they stand with the learning that is going on. If a student is NOT meeting the expectations for ANY reason – be it ability, interest, learning style, or socio/emotional issue – it us up to me to address it and assessment is data that shows me if how I am addressing it works. Evaluation is when I look critically at all of the data that I’ve culled from assessment, and reporting is how I share that with parents.

So…I don’t do zeros because of my professional ethics, which are closely tied to my core values:

- always hold on to hope for the future –> a zero in no way informs a learner of anything to do with potential for learning and change and can completely destroy any possible hope that was there.

- always teach with integrity –> giving a zero undermines my integrity as a teacher.

- always maintain the utmost respect for my students and their families –> a zero indicates to me that no communication has been made between me and my students/families about progress and how to fix things.

Very often a zero is tied to behaviour. It is a punishment for skipping class, not studying, acting jerky or disrespectful, whatever. When these things happen to me (and they do) I focus on why this is happening instead of trying to punish it. It makes more sense for me.

———————–

Podcast Map, made with Labyrinth.

Podcast Links

- You Must Learn by KRS-One

- Jose Vilson’s blog

- Hugh O’Donnell’s blog post – Help Wanted: Teachers Who Read

- Roberto Gauvin’s blog post – Ken O’Connor excellent…évidemment !!! (conference notes in English)

Scroll back up to keep reading or stay here to look at the map and play with the links to anchor you while you listen.

—————————-

Leave a Reply