Some of you know, I am currently studying at Concordia University in Montreal. This post is a start at putting together some thoughts for a presentation I will be doing next week in my doctoral research seminar. This is what interests me, this is what I want to research further, this is why I am back in school.

What is our focus in education reform?

I appreciate the time you will take to read this initial collection of ideas. I’m asking for some feedback:

– Do you think this is a valid area of inquiry?

– Have you seen/heard/participated in inquiry like this before? Tell me your story.

– Anything else?

What I’m looking at…

Two types of learning are necessary in all organizations. The first is single-loop learning: learning that corrects errors by changing routine behavior. It is incremental and adaptive, something like a thermostat that is set to turn on the heat if the room temperature drops below 48 degrees. The second is double-loop learning: learning that corrects errors by examining the underlying values and policies of the organization . (Argyris, 1993, p.5)

I’m interested in the underlying values and policies that lead to engagement in learning on an organizational level as well as in the classroom and, in particular, how each impact the other or even if they do (Lam, 2005). Specifically, I would like to examine the underlying values about the teacher’s role in the learning process, both at the organizational level and the classroom level, in order to see the effect these beliefs have on policy around educational change processes, such as education reform in Quebec.

A year ago I wrote

Tracy – Oct 11th 2007

I really think that we are focusing on the wrong things in education reform.

Recent education reform in Quebec – and I am sure it is similar in other areas – has focused on creating new curriculum for students.

Technology reforms focus on how we can best use technology in the classroom to improve student learning and to make it more authentic.

Today I responded to John Brandt’s discussion thread in the TeachingFutures wiki about his passion for making all teachers good teachers. What he wrote got me to thinking about how to do that. Is it really through curricular or technological reform? In both cases I hear proponents of the reforms saying that teachers need to change what they are doing, that they need to become more in tune with ‘the reform’.

What if we were to become more in tune with teachers? Instead of focusing on curriculum and tools with which to teach it, what if we were to focus on the teachers who will be working with the children?

In a recent post of mine I quote (then) Senator Barack Obama when he spoke in his 2005 speech, Teaching Our Kids in a 21st Century Economy, about the influence a teacher has on a child’s success. He said:

From the moment our children step into a classroom, new evidence shows that the single most important factor in determining their achievement today is not the color of their skin or where they come from; it’s not who their parents are or how much money they have.

It’s who their teacher is. It’s the person who will brave some of the most difficult schools, the most challenging children, and accept the most meager compensation simply to give someone else the chance to succeed.

Each time I read or hear that I repeat to myself

It is who the teacher is

There is a lot of ‘after the fact’ professional development for teachers. I call it ‘after the fact’ because it seems to come after curricular reform in answer to panicked teacher response to having to deal with change in how they teach.

It seems to me we are going about it backwards. I think that the reform that will finally take place that will actually stick will be when we reform the way we support and nurture teachers.

(end of post from Oct 2007)

One reason why I think it vital to focus on teacher learning is that the teacher crosses over boundaries within the educational system. Teachers have the potential to interact with people from different areas of the system, more so than anyone else. As such, they have the potential to have the most influence within the system. Think about that.

So. How do I check to see if what I think is true? That if we support and nurture teachers as a change process, rather than focusing on curricular or technological change, that we will be able to effect actual change in the system?

I want to observe organizational dynamics when it comes to learning. Observation of how learning permeates the whole system is essential to understanding our actions during times of change and reform, and possibly improving them (Collinson et al, 2006; Jackson, 2001). I want to observe the types of learning and support that are going on at the school level (admin, teacher, support staff) and the types of learning and support that are going on at the classroom level (teacher, student) and see how they relate to each other and how they shed light on the underlying beliefs and values that drive learning in Quebec. And then ask how – if? – they facilitate learning a la QEP, a la 21st Century thinking skills. I want to do this mainly through the collection of stories, narratives, about experiences of teachers in schools going through change processes, such as the QEP reforms (see here for a good description of the QEPs reforms).

I want to start off in one school system to see if there is something worth investigating further. The idea would be to find a school that is willing to enter into a double-loop learning process in relation to its organizational policies and practice around teacher learning.The ‘problem’ or hypothesis is dependent on the school system and will emerge as the study progresses. It will be about educational change and reform, but the specifics will depend on the system.

Why is this interesting?

although the school improvement programs and projects under scrutiny varied in terms of content, nature, and approach, they reflected a similar philosophy. Central to this philosophy was an adherence to the belief that the school is the center of change and the teacher is the catalyst for classroom change and development. (Bezzina, 2006, p.160)

Teachers have been described as catalysts for change, even change agents, in classrooms.

“…classroom teachers are the only real agents of school reform. It is

teachers who translate policy into action; who integrate the complex

components of standards, curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment into

comprehensible and pragmatic instruction; and who balance an

ever-changing array of political, economic, social, and educational

factors while trying to meet the individual needs of children.”~Ending the Silence by Donna M. Marriott (2003)

Yet we are change agents ‘after the fact’. Curricular reforms are handed to teachers who are expected, certainly in Quebec, to do their best with very limited resources and catch up training (see my previous posts, The Curious Case of PED Days in Quebec and How is this Normal? for more on that) MELS themselves indicate that support is essential for teachers while transitioning into the new pedagogical reforms at the secondary level, “Teachers who receive more guidance and professional development are more likely to devote themselves to implementing the QEP than those who receive less,” (Gaudreault, 2007).

Teachers are recognized as key players in the learning process, even as change agents within that process, yet they are often not involved in how education reform is implemented. I believe that if teachers were more central to the processes of reform then true changes in education could be possible. A first glance at some of the writing on the subject, as quoted above, seems to concur. I would like to investigate this more deeply through a review of the literature, but that is not enough. Observation of organizational dynamics within schools and talking with teachers and administrators about their underlying beliefs around educational reform and change is key to understanding the complexities of the educational system. As Greenwood (1993) wrote,

a study that examines underlying values, our motivators for action can help us to reflect on why we do what we do when it comes to educational reform.

Theory

Post-modern organizational development

I will be looking at the school organization through this lens, with its emphasis on relationship, contextual, narrative-based generation of ideas, and the dismissal of the notion of objectivity. They are all key elements of post-modern organizational development and discourse (Bush, 2006; Midgley, 2003; Cummings & Thanem, 2003). Another element of post-modern OD for this intervention is the concept of merging theories of change and the understanding that not one theory is relevant for all situations (Marshak, 1993). Theories and change models must be culturally significant for the system in which they are being used in order for them to generate meaningful change. (Rosen, 2006)

Within that context, I will most likely draw upon:

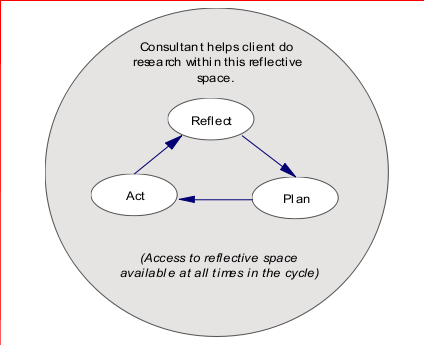

Reflective Action Research Cycle (Rosen, 2005, 2006), the structure, in which the action research cycle is subverted, to place reflection as the entry point. Reflection continues to permeate the whole process, forming the ground, the basis of the action.

Argyris and Schon Theory of Action, the mechanism through which we can become aware of why we do what we do, the actual values and beliefs behind our actions, and possibly re-align our actions with our values. It helps to connect thought to action.

There are four parts to the theory in action learning process:

(1) discovery of espoused theory (what we say we do) and theory-in-use (what we actually do)

(2) invention of new meanings

(3) production of new actions

(4) generalization of results

Appreciative Inquiry and Improvisation

Dialogue and conversation, as a tool for inquiry.

Conversation is a powerful tool for uncovering values, beliefs, and the assumptions that frame them in order to create change in organizations. Wheatley (2002)describes conversation as the way people think together. Maturana believes that conversation is what frames all of our activities together as humans. He describes the centrality of conversation to human existence (Fell & Russell, 1994) and his biological theory of cognition is, “…a reflection on how we exist in language as languaging beings, it is a study on human relations,” (Maturana, n.d., in Ruiz, 2002, ¶ 10). Maturana himself wrote “…everything human takes place in conversations…we live in conversations,” (Maturana et al, 1996, ¶ 19-21). Achinstein (2002) supports the use of conversation for dealing with conflict when she writes, “conversations about conflicts can create new ways of thinking and new ways of doing things,” (p. 435).

Conversation, when people are really listening to each other, allows for the emergence of the beliefs and values that underlie an issue for participants.

Connections to Other Disciplines

The use of conversation as a theoretical framework for making decisions is found in many helping professions. In bioethics, Hester (2004) discusses the importance of exploring methods for creating healthy dialogue from within situations rather than trying to fix them with external tools. An ethics based on contextual dialogue and relationship is becoming widely discussed within the helping professions. It is recognized that more than one perspective is necessary to come to an ethical decision (Childs, 2001; Huotari, 2001; Irvine, 2004; & Prilleltensky et al, 1996), in particular when a variety of professions with competing professional values, are working together with the same client. The importance of values, the backbone of moral ideals through which ethical decisions are made, has also been recognized as an integral aspect of decision-making in sustainability ethics, an ethic that deals with conservation and environmental issues (Tryzyna, 2001).

Preliminary outline of steps…

– Extensive review of the literature.

– Review of anecdotal evidence from within a school system.

– Conversation, through interviews and group dialogue will be the main method of gathering data.

– Suggestions for further study, possibly concrete steps for action depending on outcome of above.

Some References

Achinstein, B. (2002). “Conflict amid community: the Micropolitics of teacher

collaboration.” Teachers College Record 104 (3), 421-455.

Argyris, C. (1993). “Education for leading-learning” Organizational Dynamics, 21(3), 5-17

Bezzina, C. (2006).”The road less traveled: Professional communities in secondary schools”,Theory

Into Practice,45(2),159 — 167

Bush, G.R. & Marshak, R.J. (February 2006). Contrasting classical OD and the

post-modern reconstruction. In G.R. Bush & Associates, Revisioning

organization development: A post modern perspective, (chapter 1).

Unpublished Manuscript. (Used by permission).

Collinson, V., et al. (2006) “Organizational Learning in Schools and

School Systems: Improving Learning, Teaching, and Leading”,Theory Into Practice,45:2,107 — 116

Cummings, S. & Thanem, T. (2002). Essai: The Ghost in the organism. Organization Studies 23(5), 817-839.

Fell, L, & Russell, D. (1994), “An Introduction to “Maturana’s” Biology.” In L. Fell,

D. Russell, & A. Stewart (Eds.), Seized by agreement, swamped by

understanding. Sydney: Hawkesbury Printing. Retrieved on March 20,

2005 from http://www.pnc.com.au/~lfell/book.html

Gaudreault, S. (2007). “School organization, collaboration, professional development, and guidance: The key to success for pilot schools.” Schoolscapes 8(1) retrieved on November 7, 2008 from http://www.mels.gouv.qc.ca/sections/virage3/index_en.asp?page=rencontre_6

Greenwood, J. (1998). “The role of reflection in single and double loop learning” Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27, 1048–1053

Hester, D.M. (2004). “What must we mean by ‘community’? A processive

account.” Theoretical Medicine 25, 423-437

Jackson, M.C. (2001). “Critical systems thinking and practice” European Journal of Operational Research 128, 233-244.

Lam, J.Y.L. (2005). “School organizational structures: organizational effects on teacher and student learning” Journal of Educational Administration 43(4), 387-401

Marriot, D.M. (2003). “Ending the Silence” Phi Delta Kappan 84(7), 496-501.

Marshak, R.J. (1993). Lewin meets Confucius: A Re-view of the OD model of

change. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science 29(4), 393-415.

Maturana, H., & Verden-Zoller, G. (1996). Biology of love. Retrieved on March

20, 2005 from http://members.ozemail.com.au/%7Ejcull/articles/bol.htm

Meyer, P. (2005). Organizational improvisation & appreciative inquiry: An

exploration of symbiotic theory and practice. Retrieved on June 13, 2006

from http://www.meyercreativity.com/pdfs/Meyer_OI_AI_Paper.pdf

Midgley, G. (2003). Five sketches of post-modernism: Implications for systems

thinking and operational research. OTASC 1 (1), 47–62.

Rosen (2005). Conversations for ethical decision making in secondary schools:

A Report on exploratory sessions. Unpublished manuscript, Concordia

University, Montreal.

Trzyna, T. (2001). Raising annoying questions: Why values should be built into

decision-making. California Institute of Public Affairs publication No. 105,

Sacramento, California. Retrieved on May 23, 2005 from

http://www.interenvironment.org/cipa/raising.htm

Wheatley, M. (2002). Turning to on another: Simple conversations to restore

hope to the future. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Wheatley, M. (2004). Why I wrote the book. Retrieved on August 3, 2005 from

http://www.margaretwheatley.com/articles/whyIwrotethebook.html

Leave a Reply