This article was originally posted on July 20, 2010. I’ve recently been in conversation with a number of people about learning styles so thought it was timely to look back at this one.

A few years ago I had a series of … conversations … with my then PhD adviser about the notion of learning styles. The conversations included a few of us candidates who were also elementary or high school teachers. He maintained, and would not budge, the stance that there was no evidence to prove the existence of learning styles or the value of learning about individual student learning styles in order to improve their learning in a classroom setting. We maintained that we had seen the value in our classrooms! What was this nonsense about learning style theories being wrong? How could I give up all of the work I had been doing around learning styles in my professional and academic life (a portion of my MA included examining learning style for work in organizational development)?

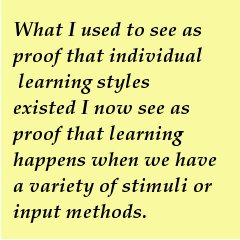

So now it’s a few years later and my coursework for this week falls under the theme of, you guessed it, learning styles. And guess what? My thoughts have changed on the subject. I realize that I have stopped testing for learning styles in my classroom. What I used to see as proof that the individual learning styles existed I now see as proof that learning happens when we have a variety of stimuli or input methods. I focus more on making sure there is a diversity of input – that the material I am presenting (if it is me presenting it) is being presented in a variety of manners. Rather than thinking of each students as having a dominant learning style, I think of how multiple forms of input help to solidify learning in everyone.

And then I did some research and found a number of documents on how learning styles can not be measured, that there is no proof of their existence. Of course, we do always find what we are looking for, don’t we? Regardless, the more I think of this, the more it makes sense.

Yes, it is possible to supply input (material, lessons, ideas, whatever) in different modalities – visually, kinesthetically, aurally, reflexively, actively, tactiley (according to dictionary.com that is a word, I’m not convinced), [add your -ly here] – and I would argue that this is a good thing BUT that the decision to do so is about good teaching and not about accessing the preferred learning styles of students.

It’s good teaching when we

- match the input methods of an activity with the subject matter that is being studied

- know that a diversity of stimuli helps to anchor what is being learned

- know that movement increases the flow of blood to the brain

- use visuals because there is research that demonstrates we need it

Another thought, not so well thought out so give me some room here but if we think that learning is a social activity, why the emphasis on individual learning styles? Like I said, it’s not so well thought out yet so all I really have is the question as a starting point.

————————

Here are some of those documents I wrote about earlier, in no particular order:

Do Learning Styles Exist? by Hugh Lafferty & Dr. Keith Burley

Matching Teaching Style to Learning Style May Not Help Students by David Glenn

Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence by Harold Pashler, Mark McDaniel, Doug Rohrer, and Robert Bjork (free pdf)

Learning Styles Re-evaluated By Rick Nauert

Doubt about learning styles by Jay Matthews

Learning Styles: A Teacher Misunderstands A Paper, and A Psychological Scientist Explains by Liz Ditz

Idea of Learning Styles in Education Further Derided by Psychology Researchers by Mike Smith

Different Strokes for Different Folks? A Critique of Learning Styles (1999) By Steven A. Stahl (free pdf)